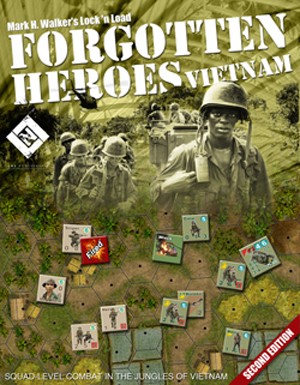

Publisher: Lock ‘n Load Games

Designer: Mark H. Walker

Year: 2011

Genre: Hex and counter based wargame set in Vietnam

Players: One or two players

Ages: 13+

Playing Time: One to three hours

Retail Price: $59.99

Forgotten Heroes: Vietnam (FHV) is a squad-level tactical wargame where each player takes on the role of the United States (and her North Vietnamese allies) or the Communist Vietnamese forces that slugged it out from the mid to late 1960s. The game’s thirteen scenarios (or fifteen for those with a preorder copy) tackle a wide range of engagements from small scale firefights to all out pitched battles with armor elements. Each turn represents two to five minutes of real time while each hex is scaled to represent an area 50 meters wide. The game uses hero cards for each side and this adds personality to the fighting forces involved.

Each game turn breaks down into three phases: Rally, Operations, and Administration.

The Rally Phase: Both players roll to see who has initiative for the turn. Once initiative is determined each player then attempts to rally shaken troops. Some units may self-rally but for the most part most can only rally if a leader, hero, or medic is in the same hex. Troops can be shaken fairly easily and tend to become rather vulnerable in that condition, especially in hand to hand combat, so how well your troops rally can be a make or break situation. To rally, the unit rolls two six-sided dice – adding leadership and terrain modifiers – and if the total is equal to or less than the unit’s morale rating they rally and are no longer shaken.

The Operations Phase: This is where the majority of the game play takes place as each player takes turns activating and taking actions during a subphase known as an impulse. The player who won initiative may activate the units in any one of his stacks but if a leader is activated then any stack adjacent to him are activated as well. In this way multiple stacks can take actions during the same impulse. These units then normally perform only one of several possible actions: spot for artillery, call in artillery, move, fire, assault move, or melee. After an activated stack has completed its action, a marker is placed on the stack to indicate the action taken and then the opposing player may active a leader or single stack. At time there may be a chance of opportunity fire during your opponent’s impulse as well.

The rules covering helicopters, tanks, and artillery are a little more complex than the standard fire combat but stem from the same basic resolution.

Players continue trading impulses until all units have taken actions or three consecutive impulses have been passed; a player may choose to pass rather than activate troops. Since each player is only taking actions with one stack (or a group of troops with a leader activation) impulses move quickly enough with very little downtime. As each player looks for ways to react to his opponent while keeping an eye peeled for opportunity fire, both players are constantly engaged.

The Administration Phase: Non-combat movement takes place and unit markers are removed or changed to reflect a new status. Then it’s time to move onto the next turn.

FHV has a lot of quick action and most games break down into a punch/counter punch as each side looks to quickly take advantage of even the smallest opportunity to snatch victory from their opponent. One great aspect of FHV is the flavor it provides as far as simulating combat in Vietnam as each of the different forces are modeled just a bit differently. The Viet Cong don’t have a lot of firepower but have a nasty habit of fading away into the jungle. This is reflected by having to roll to spot VC units even if previously spotted but they haven’t fired or moved; spotting is actually a critical part of FHV as you can’t shot at someone if you can’t see them. VC can also unleash devastating ambushes as well. U.S. Marines actually have their morale increase when shaken and can perform assault moves. NVA troops can engage in hand to hand combat and use the jungle effectively. Regular U.S. Army troops don’t receive any special benefits but at least they aren’t the poorly trained, and led, ARVN units!

Another interesting aspect of FHV is the inclusion of heroes. What makes it interesting is the fact that you don’t start the scenarios with them but each time a unit rolls a one on the damage check that unit receives a random hero. Not only does the hero receive a skill card (sixteen in all) but is actually a very tough character capable of adding bonuses in melee, rallying troops in the same hex, handling support weapons single handedly, and never becoming shaken. This reflects the sudden display of heroism under fire of fighting men throughout history; you just never know what you’re going to get. Of course, those ARVN troops have a much lower chance of producing a hero than the other three combatants.

All in all Lock ‘n Load’s Forgotten Heroes: Vietnam is an excellent game. There’s a lot here but once you’ve played through a few turns you can easily get the hang of it. I feel the game models smaller scale actions in Vietnam extremely well and, outside of a minor quibble I have here and there, is certainly worthy of a place on the gaming shelf of any wargamer and even those new to the genre with an interest in the U.S. involvement in Vietnam.

[rwp-review id=”0″]

- Chivalry & Sorcery Fifth Edition Reviewed - Nov 3, 2024

- Campaign Builder: Castles & Crowns Reviewed - Nov 2, 2024

- The Roleplaying Game of the Planet of the Apes Quickstart | First Look and Page-Through - Nov 1, 2024