Publisher: Rio Grande Games

Designer: Richard Staupe

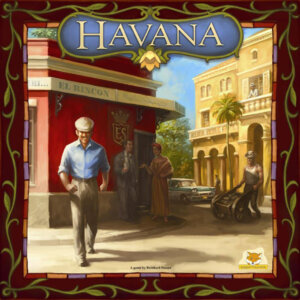

Artist: Michael Menzel

Year: 2009

Genre: Set collecting, hand management Eurogame

Players: Two to four players

Ages: 10+

Playing time: 45 to 60 minutes

MSRP: $44.95

Very rarely can I say I don’t enjoy a Rio Grande game and I think owner Jay Tummelson (with whom we’ll have an exclusive interview in the next week or so) does a spectacular job of exposing American audiences to foreign developed games by publishing them in English. Having started the review with that sentence may lead you to believe I don’t like Havana and I wouldn’t want to give you that impression at all. What I am saying is I’m a Rio Grande kind of guy and, even though I may not have my socks knocked off by every single release, I can honestly say that every RGG game I’ve played wouldn’t rate lower than a six on my personal review scale. The number of Spiel des Jahres winners Rio Grande publishes in English is a fine indicator of the quality I’ve come to expect from RGG. Havana, which saw a lot of demo play at this year’s Origins, is another example of that quality.

I know that many people are comparing the game to the board game Cuba. Many people think it’s similar to the card game San Juan, which is a simpler version of Puerto Rico, and Havana is essentially a stripped down card-game version of Cuba. I have to wonder if those writing about Havana have actually played either game. In truth, while Havana maintains some of the basic theme of Cuba, play departs rather significantly from its well received “parent” game.

Game play revolves around the mechanic of simultaneous action card selection from identical sets of decks. Each player has a set of 13 cards that individually allow the player to take specific actions. On the first round of play, all players will secretly choose two cards to play. In addition to the card’s function, the numerical combination of cards played is important (e.g. two cards with a value of 1 and 8 each, result in a value of 18) as the player with the lowest combined number acts first. Turn order for that round is determined simply based on the two cards chosen. Then, in order, each player resolves the actions of their cards.

Actions primarily allow the player to gather various types of resources or mechanically alter specific rules of the games (such as making that player temporarily immune to thieving and taxes) while looking to acquire victory points. Once a player has resolved the action portion of the cards, they may purchase any available building. Winning the game is solely based on the victory value of the buildings you own. The number of players will determine the victory points needed to win.

Starting on the second turn, and every subsequent turn thereafter, each player publicly chooses one played card to discard and secretly chooses a new card for next turn. This gives later players in the turn a sense of what earlier players might be doing. and helps balance the advantage gained by going early in the turn, since you know one of the actions your opponent is planning to perform. Granted you’ll eventually have only a few actions you may perform based on your discards but once you’re down to two action cards in your hand you’re able to pick up all your discards and place them in your hand once again.

The game play is silky smooth due to rather limited options on any given turn, so play rarely slows down because someone is going to sit and analyze each and every option. But, while game play is slick, it can also be a bit frustrating – if someone plays a poorly planned card it can really toss a wrench into victory for anyone.

This may expose the biggest flaw of the game. The game is unforgiving of mistakes and, while it is extremely easy to learn the rules and I would consider it more or less a “gateway” game, you might not want to break it out for players who aren’t willing to give a little thought to the overall situation on any given turn. Some actions might seem like an excellent choice to perform while the reality is quite the opposite if the moment isn’t right.

Havana has a lot going for it. First and foremost, it is a short game. Even the first time out with new players you can expect to finish well within an hour and the number of players does not significantly affect the time it takes to play from what I’ve seen. The art style, similar to that in Cuba, is rich and game play enhances the theme rather than obscuring it. Also, many gamers will appreciate that Havana breaks from a common trend we see in many games recently where there is limited or no player interaction; many of the cards allow players to steal from each other or to adjust the availability of buildings, often specifically to deny an opponent. This interaction gives the game a nice competitive edge.

Fans of quick card games are going to find Havana to be an entertaining new diversion. You might not be too excited if you like a longer and meatier game to savor over an entire evening or if your group is made up of players who aren’t willing to invest a bit of observation into actions taking place other than their own. The co-op crowd may be turned off by the interaction since this isn’t part of the “everyone wins or loses” stable of games. There is a bit of luck involved but the clever and thoughtful player will surely thrash their opponents most of the time.

In the end, Havana is a strangely elegant game that is easy to teach new gamers in just minutes while also appealing to those who are caught in the relative limbo between “gateway games” and much more complicated fare.