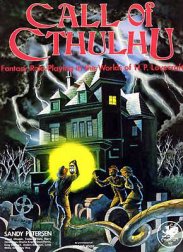

I still remember the first time I held Chaosium’s Call of Cthulhu roleplaying game in my trembling hands. Alright, I’ll be honest, my hands weren’t really trembling. They weren’t trembling because at that moment, back in 1981, I had no idea of what in the world Cthulhu could be or who H.P. Lovecraft was. Yet there I was standing in the small game shop, which was the main recipient of my hard earned cash for my first couple of years in high school, wondering what to make out of this rather shallow box that promised to transport my gaming gang into a world of suspense and terror.

If I knew at that moment all the years of fun and entertainment that little box would help lead to, there would have been absolutely no hesitation!

Keep in mind CofC (as we came to call the game) wasn’t my first RPG rodeo. We had played AD&D, a bit of Gamma World, some Traveller, and two of our pals – Scott Weigel and Tim Felan – ran Top Secret. You can see that TSR was behind most of our roleplaying systems, outside Traveller, during our first year in high school. So when I cracked open Call of Cthulhu for the first time it was something very, very different. And we liked it.

At its heart CofC’s mechanics are driven by a simple percentage skill system, which is easy to learn yet never modeled anything unsatisfactorily or messily. Attributes did add 3D6 rolls to the mix, a slight hiccup, but one that still worked well. Here was a game where the

characters had skills which made them a bit more unique compared to the generic attribute based roleplaying game systems. This was a first for us although, unknown to ourselves at the time, the mechanics were a simplified version of the Basic Role-Playing system used in Chaosium’s own RuneQuest. So I did mention we liked it?

We liked it a lot! Nearly 15 years of liking it a lot!

For those gamers out there who may have been living in a cave over the years, the basic concept behind Call of Cthulhu, as well as Lovecraft’s literary mythos, is that the universe is much more horrifying than we can possibly imagine. The world was once ruled by vastly powerful and utterly alien beings. These beings still lurk outside the edges of our world, and make contact with humans (normally beginning in dreams) who are desperate enough attempt to deal with them. Normally these same humans are simply unknowing pawns who willingly pay the price of their sanity, and usually their lives, in the quest to bring these beings back into our own world.

They were not composed altogether of flesh and blood. They had shape…but that shape was not made of matter. When the stars were right, They could plunge from world to world through the sky; but when the stars were wrong, They could not live. But although They no longer lived, They would never really die. They all lay in stone houses in Their great city of R’lyeh, preserved by the spells of mighty Cthulhu for a glorious resurrection when the stars and the earth might once more be ready for Them.

H.P. Lovecraft – “The Call of Cthulhu”

In the Lovecraft mythos, the vast majority of people in the world live simple, normal lives, completely unaware of their insignificance in the universal scheme of things – which seems to be an accurate depiction of Lovecraft’s own worldview – knowing little of the forces working to bring an end to our reality. A very few souls gain awareness of how the universe really works, and those few become the heroes of the story.

The players take the roles of these ordinary people drawn into the realm of the mysterious: detectives, criminals, scholars, artists, war veterans, you name it! Often, happenings begin innocently enough, until more and more of the workings behind the scenes are revealed. As the characters learn more of the true horrors of the world and the irrelevance of humanity, their sanity (represented by ‘Sanity Points’, abbreviated as SAN) inevitably withers away. The game included a mechanism for determining how damaged a character’s sanity is at any given point; encountering the horrific beings usually triggered a loss of these precious SAN points. Also, to gain the tools they needed to defeat the horrors – mystic knowledge and magic – the characters had to be willing to give up some of their sanity.

For those grounded in the RPG tradition, the very first release of Call of Cthulhu created a brand new framework for gaming. Rather than the traditional format established by Dungeons & Dragons, which often involved the characters wandering randomly through caves or tunnels and fighting different types of monsters, Sandy Petersen introduced the concept of what he called the Onion Skin: Interlocking layers of information and nested clues that lead the Player Characters from seemingly minor investigations say into a missing person to discovering mind-numbingly horrifying, global conspiracies to destroy the world. Unlike its predecessor games, CofC assumed that most investigators would not survive, alive or sane, and that the only safe way to deal with the great majority of nasty things described in the rule book was to run away. A well-run CofC campaign should always engender a sense of foreboding and inevitable doom in its players.

The style and setting of the game, in a relatively modern time, created an emphasis on real-life locations and situations, character research, and thinking one’s way around trouble. There were to be no big toe-to-toe “boss” battles in the realm of CofC! Hack-N-Slash type players were sure to be toast. Not only would the players be squashed like flies by any Great Old One once they came within sight, that very glimpse would send their minds reeling and leave them babbling, slathering, insane idiots.

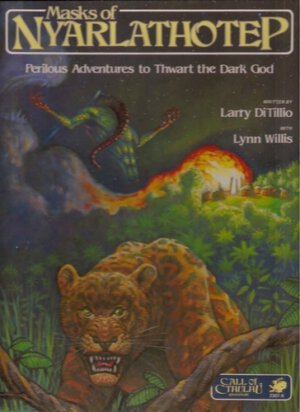

The first book of Call of Cthulhu adventures was Shadows of Yog-Sothoth. In this work, the characters come upon a secret society’s foul plot to destroy mankind, and pursue it first near to home and then in a series of exotic locations. This template was to be followed in many subsequent campaigns, including The Fungi from Yuggoth (later known as Curse of Cthulhu and Day of the Beast), Spawn of Azathoth, and possibly the most highly acclaimed of all, Masks of Nyarlathotep! Many of these seem closer in tone to the pulp adventures of Indiana Jones than to H. P. Lovecraft, but they are nonetheless beloved by many gamers. In fact, even though we played through Masks of Nyarlathotep more than twenty years ago, that campaign remains burned into the memories of my friends for whom I ran the campaign.

Ask Elliott about the classic “truck VS cultists chase” some day…

Shadows of Yog-Sothoth is important not only because it represented the first published addition to the boxed first edition of Call of Cthulhu, but because its format defined a new way of approaching a campaign of linked RPG scenarios involving actual clues for the would-be detectives amongst the players to follow and link in order to uncover the dastardly plots afoot. Its format has been used by every other campaign-length Call of Cthulhu publication since.

The standard of the included ‘clue’ material varied from scenario to scenario, but reached its zenith in the original boxed versions of the Masks of Nyarlathotep and Horror on the Orient Express campaigns. Inside these one could find matchbooks and business cards apparently defaced by non-player characters, newspaper cuttings and, in the case of Orient Express, period passports to which players could even attach their photographs, almost bringing a Live Action Role Playing feel to a tabletop game. Indeed, during the period that these supplements were produced, third party campaign publishers strove to emulate the quality of the additional materials, often offering separately-priced ‘deluxe’ clue packages for their campaigns.

Additional milieu were provided by Chaosium with the release of Dreamlands, a boxed supplement containing additional rules needed for playing within the Lovecraft Dreamlands, a large map and a scenario booklet, and Cthulhu By Gaslight, another boxed set which moved the action from the 1920s to the 1890s.

Additional milieu were provided by Chaosium with the release of Dreamlands, a boxed supplement containing additional rules needed for playing within the Lovecraft Dreamlands, a large map and a scenario booklet, and Cthulhu By Gaslight, another boxed set which moved the action from the 1920s to the 1890s.

Roleplaying games are, to me at least, always about creating dramatic scenes, generally with a narrative flow. A rulebook, thus, should provide tools to create narrative dramas. That’s what these rules felt like – tools for roleplaying, perfectly honed to set up a framework within which drama can take place. Characters in this game for once were NOT multi-layered living personalities with life histories longer than your arm, which inevitably fail to be easily manipulated into the needs of the drama taking place. No, here PCs were merely two dimensional literary figures, whose lives never extended beyond the needs of the story. For once, this was a rules system that realized overly complex character creation can be just as destructive to good roleplaying as simplistic ones. The big “idea” behind CofC was that the characters weren’t necessarily the stars of the story; the story was all important!

Moreover, the tools included were perfectly attuned to the source material. If the character sheet included a skill, wasn’t because it seemed logical, or because other games had it, but because it was important in the kind of dramas you were trying to create. And that’s the feeling you got with every single rule in CoC – that it’s there precisely because it played a key role somewhere in the source material. And, what is more, the rules also felt like they were the absolute minimum of complexity – anything that didn’t appear in the source material, didn’t appear in the rules.

That might sound easy, but it isn’t. Not at the level of perfection CofC achieved. There has never been before, nor likely never be again, another game that recreated its source material with the same level of depth, passion and life as Call of Cthulhu.

This is what makes it a true gaming classic!

What memories this game holds. By far the most excitement and fun I have ever had playing a game. I believe that once we played this, we never played another game of D&D again (willingly). Ever try to light and throw a stick of dynamite from the back of a pickup truck, while being chased by angry cultists with guns, while one of your companions is unconcious and bouncing around the back of the truck, and the other one (who was driving) just got shot and was passing out too? Geeze. Or the time our buddy got impaled and killed by a fence by climbing it in the rain. We couldn't get him down, so we left his body hanging there. His zombie pursued us from adventure to adventure, showing up at the worst times possible as he tried to extract his revenge for leaving him there. It was the best, Jeff was the GM to end all GMs. I never played with another GM who could bring all the players so much into the story.