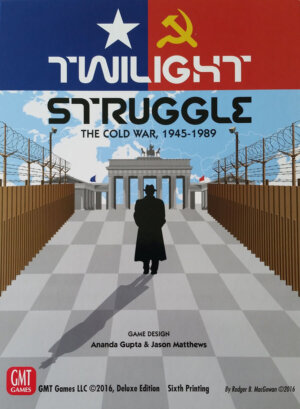

Publisher: GMT Games

Designers: Jason Matthews and Ananda Gupta

Artists: Viktor Csete, Rodger B. MacGowan, Chechu Nieto, Guillaume Ries, and Mark Simonitch

Year: 2005 (Deluxe edition reviewed, 2009)

Players: Two players

Ages: 14+ (my estimate)

Playing time: Two to three hours

MSRP: $65.00

Designed by Jason Matthews and Ananda Gupta and originally published in 2005 (followed by the currently available Deluxe version in 2009) Twilight Struggle is a two player game simulating the Cold War in which one side takes on the role of the United States and the other, the USSR. Each side is battling for ideological domination of regions of the world through the play of event cards, realignment of influence, and coup attempts. The game lasts ten turns, each representing an approximate five-year stretch, beginning in 1945 (following the end of WWII) and running through the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1989.

Many people have the impression that Twilight Struggle is a war game. Sure, the components and look of the board would lead some to that conclusion but when it’s all boiled down we’re looking at a strategy game masquerading as a traditional war game.

The map is divided into regions and within those regions are the nations which each superpower is vying for control. Some of these are notated with a different color as “Battleground” nations, which take on more importance. Nations are also connected with lines, sometimes not geographically but by political spheres, and certain actions require checking on the status of countries which are adjacent.

As usual, the components are of the same high quality as we’ve come to love from GMT.

Each turn plays out as follows:

Improve Defcon Level: How close the world is to nuclear war is represented by the Defcon Level. If Defcon ever drops to one the game will end and the player that caused the drop automatically loses. It’s one thing to bring the world to the brink of Armageddon and something else to actually end the world…

The game begins at Defcon 5 and through events and coup attempts will degrade. At the start of each turn the level will increase (move toward peace) one level. Each player much perform military actions equal to the Defcon at the beginning of the turn.

The Defcon Level also restricts what regions of the world coups may be attempted.

Deal Cards: Beginning with the Soviet player, each player is alternately dealt a card to bring their hand to eight cards. From turns 4-10 each player’s hand is increased to nine cards.

Headline Phase: Each player must choose an event from their hand to be played. The event with a higher operations value takes place first. In this way players must have at least one event occur each turn.

The Action Rounds: This is where you find the real meat of the game. The cards represent a different event that took place during the Cold War while a handful are used for scoring. The event cards also have an operations point value as well. When a card is played the phasing player makes the choice of whether the event takes place or if the operational points will be used. If the card event is used, the player simply follows the instructions on the card. This could be something along the lines of NATO being formed, the Korean War breaking out, or some other major or minor occurrence that took place historically.

It’s important to note that the cards are divided into three piles: Early, Mid, and Late War cards. The first three turns are the Early War, the next three are Mid War, and the final four turns are Late War. Events from the late war will not take place early in the game so you won’t run across Reagan calling for anyone to tear down the Berlin Wall, but it is possible that Early War events won’t take place until later in the game – once, while playing, the Korean War didn’t occur until the early 1970s…

Many of the events are one time affairs and once the card is played as the event it is discarded from play.

Some cards are scoring cards and these must be played on the turn they are dealt. Players score points based on the number of nations they control in the particular region on the card and if those countries are considered battleground nations. Battleground nations carry more importance than others. Both players receive points so it is not unusual for the side to play the scoring card to end up on the short end of the stick as far as victory points from the card.

A player need not activate the event and use the operational points from the card instead. If the event displayed is that of your side it doesn’t take place but, if it belongs to your opponent, it will and the phasing player decides if the operation points are used prior to or after the event. These operation points can be spent in a variety of ways.

Players may influence a nation. While you have to have influence in an adjacent nation, you can place influence in any country even if your opponent already has their own influence there. Normally influence is purchased on a one operation point/one influence point trade but the cost can increase depending on if your opponent already has influence in that particular nation.

Players may also attempt a realignment of a nation. This is simply a die roll and, if successful, removes your opponent’s influence without any influential gain on your part.

Operation points can also be spent on a coup attempt. This uses all the operation points on the card and success is based upon the stability of the country. Stability is multiplied by two and a die is rolled. The result of the roll and the operation points of the card are added together. The modified stability of the country is then subtracted from the total and if there is a positive result remaining that is the amount of influence your opponent loses. If all of your opponent’s influence is removed – and there are still points remaining – then you gain that amount of influence in that nation.

Depending on the current Defcon Level some regions may not have coup attempts made. For an example, at Defcon 4 you may not attempt a coup in Europe.

One last action can be played with an event card, outside of activating the event or using operations points, and that is the Space Race. This is a very abstract but you can essentially discard into the Space Race and roll a die. If you score the desired result, you move one step closer to putting a man on the moon. You can score a few victory points in this way and some steps along the way provide a small bonus that stays in effect until your opponent also reaches that step in the quest for the moon.

It’s important to note that when a card is discarded into the Space Race the event does not take place regardless of who the event would benefit. This is an excellent way for you to keep important opponent events from taking place until at least a reshuffle of the deck. Only one card can be played toward the Space Race on a given turn (outside of one step once reached that allows two) so it isn’t as if you can get away with dumping a bad hand of cards into space…

Check Military Operations: This is the Cold War and you just can’t sit back because your military chiefs just won’t allow it. Each turn both players must engage in military actions equal to the Defcon Level. If those actions don’t take place that player is penalized victory points equal to the number of actions not taken.

Flip the China Card: China, and its part played in the Cold War, is abstracted with a powerful card called the China Card. It begins in the USSR player’s hand but, once played, is handed over to the US player. The card is sent for that turn but is flipped up to be playable at the end of the current turn. The China card can ping pong back and forth between the opponents.

At the end of the ten turns, the player with the most victory points wins. If either player gets more than twenty points during the course of the game they also win in that way; and, of course, if Defcon reaches 1, the nukes start flying and whoever triggered the final confrontation is the loser.

So what are my thoughts on Twilight Struggle?

Simply enough this is more than likely my favorite game that currently makes its way to my table.

The game simply oozes theme as each turn is loaded with historical events taking place and a punch/counter punch sense of the real Cold War emerges. There’s real tension in the game as the number of options available during each action round are many and you just never really know what cards are in your opponent’s hand and what tricks are up their sleeve.

At the start of the game, players focus more or less on Asia and Europe since these are the scoring cards that could be in someone’s hand. As time progresses, and new cards are shuffled into the active deck, focus shifts to the Middle East and South America. Finally, Africa and Central America are added to the mix. While this follows the real-life course of the Cold War you aren’t just replaying history as it unfolded. Many times crisis will break out where none took place during the Cold War, but the results are realistic and feel as if they could have happened.

Some people believe Russia has a slight advantage in the game but I’m not sold on that line of thinking. It’s true that early on the USSR does have the advantage but a smart American player can counter or at least keep things from getting out of hand. As the game goes on and the Mid War (and especially Late War) cards enter play balance evens out and finally tilts directly to the US. This isn’t to say that the Russians can’t win late but it takes a watchful and crafty player to offset the turning of the tide.

Some people believe Russia has a slight advantage in the game but I’m not sold on that line of thinking. It’s true that early on the USSR does have the advantage but a smart American player can counter or at least keep things from getting out of hand. As the game goes on and the Mid War (and especially Late War) cards enter play balance evens out and finally tilts directly to the US. This isn’t to say that the Russians can’t win late but it takes a watchful and crafty player to offset the turning of the tide.

All in all a good player will win more often than not regardless of which side he plays.

At first glance Twilight Struggle may seem a bit complex but it really isn’t. Once some basic concepts of the game are understood, things fall into place and it doesn’t take much more than a couple of turns or so to get into the flow. I’ve personally taught the game to a few people (my mother included) and it never took more than thirty minutes of gameplay before just about everything clicked. Of course, for the extremely casual gamer – or someone who gets antsy if a game last more than sixty minutes – this isn’t going to be their cup of tea. Early games can last upwards of three hours and, although I love to sit down to a great epic afternoon tilt of any kind, some folks may not feel up to the time investment. After subsequent plays you can normally get a game finished in around two hours; Elliott and I easily played back to back games in Chicago and we probably spent no more than three and a half hours with both games.

I have to say that Twilight Struggle easily earns its top five ranking on Board Game Geek. It is a classic that will appeal to any gamer who loves a fantastic strategy game with tremendous theme. Some might quibble with my final score on the game but for my money there aren’t any games in my collection that I would rank higher than Twilight Struggle!

- The Old Margreve for Tales of the Valiant Reviewed - Apr 27, 2025

- Marvel Comics for April 30th, 2025 - Apr 27, 2025

- DC Comics for April 30th, 2025 - Apr 27, 2025