You slip a sharp blade between the box and lid to cut the shrinkwrap, pull the thin plastic off, open the box, and breathe deeply of the aromatic inks and glue. Ahh. Pop the pieces out of their frames, sort them by color and use, and settle down for a serious read with a new rule book.

Life just doesn’t get any better, does it? Unless you add beer. But I digress.

Take a set of rules, the board and bits, set them up, have your gaming gang stop by, and you have what you need for a damn fine evening. But the question I have here is this: what’s the story?

I ask that question because I know—as a game reviewer and game explainer (I’m the guy hosting the game day, so I’d better be prepared)—that the first step to getting people interested in a game is to describe the game’s narrative frame. You’re all epidemiologists trying to stop multiple global disease outbreaks. You’re rats escaping the Titanic. You control this army as it moves across the checkered field to engage the other army. And so on. The game has a story it wants to tell.

Frequently, that story is the theme, and when we talk about how well the theme is implemented we’re talking about how well the storyline syncs up with the rules. Humans tend to like stories a whole lot more than they like arbitrary decision trees and operations (though we do seem to like those, too, or we wouldn’t have been gaming for as long as we have), so even a thin veneer of story helps to engage players. The story the game is telling influences design and marketing choices. I might not like managing resources in medieval Europe or the Industrial Age, but if we’re mining ore around Saturn, well, that’s a game I could play. With this level of story, however, the game exists as an abstraction. We look at the story, at the rules, and we’re either interested in playing—to some degree or other—or we’re not.

Once you’ve got the gang settled around the table and the pieces are out, you start a different story, though. This story relates closely to the story the game wants to tell, but now there’s a bit of separation. As the game is played, the story unfolds. It’s the story of the blue monkey opening the most cages, or the story of how my group of explorers picked up the most loot on the island. The game wants to tell a story, but the story of each playing extends—or changes, or subverts—the story that’s built into the game.

This second level of story is where most of us decide whether or not we like the game. How did the story work, now that we’ve experienced it? Did the intersection of rules and story work? Someone might find the rules intriguing, someone else might find the completed story compelling. And it’s this story that will be different every time. At least, you hope so. And you hope the story is different for good and compelling reasons. Randomness and luck work pretty strongly against coherent storytelling. Candyland, Sorry!, and Fluxx (among others) have their detractors because the story is outside of the player’s control. Deeply strategic decisions—or even meaningful tactical ones—let players build a satisfying story. And maybe a victory in the process.

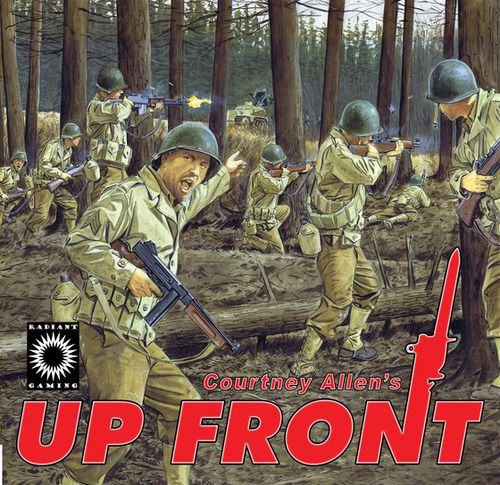

And then there’s one more level of story, one that hardly involves the game at all: What story takes place among the players? This story is part of the meta-game, as some people refer to the time and space above the board and outside of the rules. Who sits down at the table? This might be the evening when your friend of ten years slaps the board from the table, or someone turns to their spouse and says that they can’t keep living under the same roof. Those are stories that have nothing to do with game design, but they certainly influence play and how the game unfolds that particular time. Remember, though, that we can—and sometimes need to—keep the second and third levels separate. When we’re up to this level, our experience of the second level can be deeply changed. Memoir 44 might be entirely ruined for you by the guy making shooting noises every time he fires at your position. And then he complains when one of his units gets taken out… Not a good story.

At least, not a good story to be a part of at the moment, but a great story to tell later. Keep in mind, though, that how you experience the second level of narrative, the board level, can be profoundly influenced by the above the board level. It’s easy to walk away from a game feeling cranky about the game when what you’re really cranky about is the player to your right who would spend twenty minutes on a move and then make a play just when you were going to get up to get another drink. So then you’d rush your move just to make up for the foot-dragging, and you ended up losing badly. Of course, the game might legitimately be a bad game, but the story you got caught up in was much worse.

When we think about games and their stories, we’re thinking about a nicely complicated interweaving of narrative and activity. We need to think about narrative because we won’t win every game we play, but the story of the game—at one or more of the three levels—draws us back to the table. It’s why I think that single-minded pursuit of victory doesn’t entirely explain why people like to play games. I don’t know about you, but I’ve heard—and been a part of—some great stories, and the promise of more stories makes me want to open up a few games and unfold a few extra chairs for friends.

- Titan Comics for February 21st, 2018 - Feb 17, 2018

- The Gardeners and the Panda?: A Review of Takenoko - Jan 25, 2012

- You Made a Time Machine Out of a DeLorean? Back to the Future – The Card Game Reviewed - Jan 8, 2012

I very much agree. That’s what makes designing so difficult. Making up a bunch of actions to do is easy–putting together a compelling story that envelopes interesting choices is hard.

Phillip, thanks for the comment. The reverse is true, too: it’s fairly easy to tell a story, but hard to build game mechanisms around the story. And it’s hard to tell a good story, of course. Getting the two pieces to sync up, that’s the compelling task.